Disappearing Witness by Gretchen Garner. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Gretchen Garner thinks documentary photography contributes something that is worth preserving.

For much of the 20th Century, Â that would have seemed like a ridiculously self-evident perspective. Documentary photography, or more precisely, what Garner refers to as spontaneous witness, dominated photography for most of the past century in one form or another.

Garner begins and ends her book with a line from a poem by Wallace Stevens: “It must be this rhapsody or none. The rhapsody of things as they are.”

(Interestingly, another recent book employs that same phrase in its title [although attributed to Sir Francis Bacon in a slightly different quote: “The contemplation of things as they are, without substitution or imposture, without error or confusion, is in itself a nobler thing than a whole harvest of invention”.] That book, Things as They Are is a compilation of reprints of photojournalism stories since 1955, as they were originally published. )

Improvements and innovations affecting cameras, film, printing processes and publishing set the stage for the photography of witness. But, the turbulent social conditions of the past century certainly had at least as much to do with the rise of documentary or witness photography.

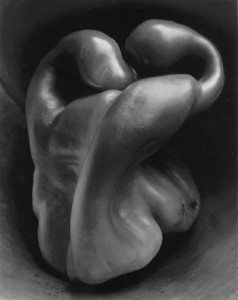

Pepper #30, Edward Weston. Weston was a staunch proponent of "straight" photography. Not a documentarian, his images still relied on his ability to capture his personal vision of things "as they are." Copyright Edward Weston

Two world wars, a worldwide depression, the cold war, globalization, battles over civil rights, urbanization, industrialization, disaffection and disillusionment with the “American Dream”…all of these created an environment perfect for stories that could be told visually. When journalists set out to tell these stories, the technology and the marketplace were ready for a visual presentation.

The influence of photographs as documents even came to dominate the art world. Images that were never intended to be displayed as art were declared as such by curators and collectors. And, photographers, many of whom had originally trained as artists, were only too happy to expand their market and accept the rewards that came with recognition from the art world.

The truth is that the history of the 20th century was told more by pictures than by words. It was the first visual century and it will be forever defined by still photographs.

Yet, Garner notes (even laments) that even as witness photographs came to dominate journalism, popular culture and art, the winds of change were already blowing. The dominance was short-lived. The single-greatest impact was the collapse of the marketplace. General circulation picture magazines, such as Life and Look, turned out to have a relatively short lifespan. Life lasted less than 40 years and for many of those years it struggled to retain circulation and control costs.

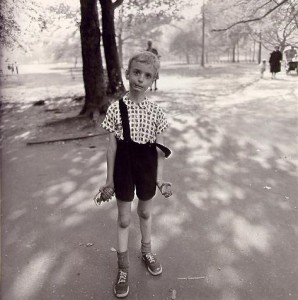

Exasperated Boy with Toy Hand Grenade, 1962, by Diane Arbus. Although her approach was far different from the classic documentarians, Arbus still used her camera to document the world as she found it, while incorporating her own personal vision into the photographs. Copyright Diane Arbus

The mass circulation picture magazines could not compete with television, which became the dominant market for the visual reporting of current events. At the same time, the rise of popular culture and in particular, that of pop music, had a profound influence on photojournalism. Rolling Stone, which has now outlasted Life, embodies the changes in the way the publishing world approached photography.

Certainly the general circulation picture magazines had always focused heavily on movie, stage and musical stars. But with Rolling Stone, the emphasis was inverted: instead of a general news magazine with celebrities thrown in as seasoning, the magazine made the music industry and its stars the main event, with occasional forays into political news.

With that came a new style of photography (or perhaps it would be more accurate to say a revival of an old style). The photographs that define Rolling Stone (personified by Annie Leibovitz) are staged, created images that make no pretense of representing actual events.

Rolling Stone was followed by People, Us and dozens of others. Today, there may be more magazines published than ever before. But precious few offer anything other than an occasional marketplace for documentary or witness photography.

More is at work than simply the commercial marketplace. Changing styles in the art world have also had an impact as the same critics and curators who had once elevated the photography of witness to high art, looked for new innovators and perspectives. Still, the photograph as a social document continued to dominate well into the 80s and beyond, although as Garner and others have noted, it was a more introspective, personal and idiosyncratic version of witness, which is generally traced to Robert Frank’s The Americans.

The great photographers of the 60s and 70s were certainly “witness” photographers: Diane Arbus…Gary Winogrand…Lee Friedlander…Elliott Erwitt…

Charleston, South Carolina. Robert Frank's personal vision of America in the 1950s broke new ground and influenced generations of photographers. Still, his deeply personal vision of America remained firmly grounded in a straight, documentary tradition. Copyright Robert Frank.

Even the New Topographics photographers like Stephen Shore and Lewis Baltz and Robert Adams were clearly operating in the tradition of witness photography.

But, as Garner follows the trajectory of photography into the 21st century (and by that I mean mostly those photographs that are considered by curators and collectors today as “art”) she notes that the photographer as witness to the world (whether as an objective journalistic witness or as a subjective observer) has fallen out of style.

Instead, it is the directorial photograph that is currently in fashion. Garner is no critic of this directorial, story-telling style. Â In fact, she treats the practitioners with respect and appreciation. I don’t think her point is that it must be one or the other.

William Mortensen's style of directorial, heavily manipulated and fantastic photographs were strongly rejected by the "straight photography" movement. Mortensen was effectively written out of photographic history for decades as a result. The Pit and the Pendulum, copyright William Mortensen

Too much damage has been done over the short history of photography by the “tastemakers” who (in the United States at least) conspired to write the tradition and personalities of photographic manipulation and fictional story-telling out of the history and out of the marketplace (William Mortensen being the best-known victim)

Of course, there are still plenty of photographers practicing some form of witness photography. The fact that the market has evaporated and appreciation for spontaneous witness has fallen out of favor, does not necessarily mean it has lost its value.

“The rhapsody of things as they are” has become much more difficult to perform in the 21st century. The rise of digital photography raises challenging questions about what comprises “witness” photography today.

Jerry Uelsmann was one of the first photographers to revive and champion the created image, rather than continuing in the tradition of "witness" photography that dominated most of the 20th century. Untitled, 1996, copyright Jerry Uelsmann.

Critics are right to point out that many of the iconic “documents” of the 20th century were tainted by direction and manipulation.

The best known documentary project, the depression-era Farm Security Administration photographs, were never a purely objective, honest portrayal of American life. The photographers were in the employ of the government and instructed to bring back pictures meant to satisfy the political agenda of the Roosevelt administration. True, most of the photographers shared the political views of their employer and were willing collaborators.

But, those failures do not negate the social and artistic value of the work that was done.

Garner takes a look at contemporary photographers (or perhaps it might be more accurate to say, photographers whose personal styles coincide with the tastes of contemporary curators and critics) and points out that many use their photographs and digital technology to “witness” the world of imagination, fantastic visions and inner psychological conflicts.

These photographers have added greatly to the richness of the photographic experience. But, neither their creative vision, nor the ease by which photographers today can manipulate digital images should cause us to reject the value of photographs to continue to offer witness to the world we live in.

There must always be a place for photographs that attempt to honestly document “things as they are.” To lose that because it has gone out of style would be a tragedy and that, I believe, is Garner’s point.

Pingback: Is Fine Art Photography Dead? | Unfocused Blog