The Photograph by Graham Clarke

The Photograph by Graham Clarke is the first of three planned books on photography in the Oxford History of Art series. The second is American Photography by Miles Orvell, which I’ll review at a later date. The third volume, Contemporary Photography, has yet to be published.

I was immediately disarmed when I started this book and read in the very first paragraph of the introduction Clarke’s candid acknowledgment of the inadequacy of a history of photography that is limited to 130 photographs in the entire book. In fact, what is also interesting is that while those 130 photographs include many classic images common to virtually any history, there are a number of selections that are a surprise.

Candidly, the book could do with a few more images. It seems as though the constraints of the overall series may have limited the selection a little too tightly. Some of the omissions are glaring. For example when Clarke devotes a chapter to “The Photograph Manipulated” he makes no mention of and uses no images from Jerry Uelsmann.

The Flatiron, 1903, by Alfred Stieglitz

Naomi Rosenbloom’s World History of Photography can be a gentle and relaxing stroll through the history of photography. But, Professor Clarke’s  interpretations occasionally made me want to scream, as when he discusses Alfred Stieglitz’s relationship with New York in his chapter on “The City in Photography.”

Clarke begins with an exploration of Stieglitz’s The Flatiron (1903), which he says, Stieglitz viewed as an image of the “new America in the making.” Clarke describes the image as “ethereal” and observes that Stieglitz “denudes the building of its solidity and function as an office. The realist context gives way to an imposed ideal frame of reference.”

A bit dense perhaps, but certainly accurate.

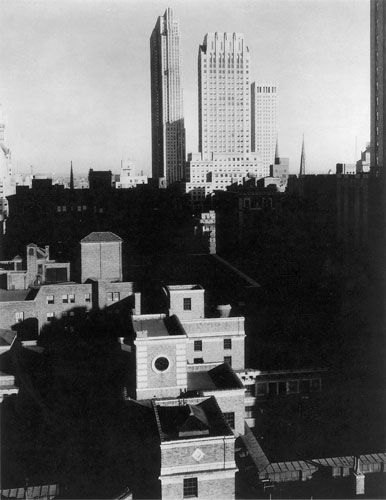

Then, Clarke turns to another image of the city taken some thirty-two years later: From the Shelton, Looking West. The image, Clarke says, is “sombre, still, bleak, and melancholy.

“Thus Stieglitz was effectively defeated by a city he sought to unify and idealize according to an underlying philosophy of meaning,” Clarke writes. “He rendered the social and human context neutral, and increasingly faced the material evidence of the city, not as symbolic image, but as raucous and callous reality of the kind we find in the paintings of the Ash-Can School, and in the naturalist writing of Stephen Crane and Theodore Dreiser.”

Not content to end there, Clarke concludes that this is “a made world always hovering on the edge of meaninglessness.”

From the Shelton, Looking West, circa 1935, by Alfred Stieglitz

This might be credible, if the image Clarke chose was remotely related to his conclusions. But, From the Shelton, Looking West is an absolutely beautiful image of sunlight playing against the sides of buildings. It may be “still” but it is most certainly not “bleak” or “melancholy.” (I apologize for the poor quality of the reproduction on this page, there were limited choices available on the internet, including some very savagely cropped versions that I refused to consider) Clearly, in the decades separating The Flatiron from From the Shelton, Stieglitz did more than probably anyone else to lead photography out of pictorialism  to the sharply focused, “straight” approach of photographers like Paul Strand, whom Stieglitz had championed.

The differences between the two images are evidence of how far photography advanced during those decades and how much Stieglitz’s own images reflected the revolution in seeing that he helped start. But there is nothing “raucous” or “callous” about the image and if it is not a symbolic image, I can’t imagine what is.

Stieglitz was never a chronicler of the human condition. Even The Steerage, which is about as close as he ever gets to social commentary, is as much about abstract shapes and interplay of light as it is about the passengers.

Clarke says of The Steerage, “there is no social or documentary concern. Stieglitz saw a picture of ‘shapes’, not of human figures, and concentrated on an abstract pattern which for him suggested the feeling he had about ‘life.’ The abject condition of the figures in steerage is completely ignored.”

Other authors might view Clarke’s assessment as a bit harsh. Ian Jeffrey, for example, sees the image as equally about composition and shapes and about the human condition. Jeffrey claims Stieglitz “warmed to the common people from whom he was cut off.”

The point really is this. Clarke’s strained attempt to inject social or personal commentary into From the Shelton seems to miss the point of the picture. It’s particularly perplexing because he certainly recognizes the purity of vision in The Steerage.  I see From the Shelton as a commentary about the city to the same degree that I see Weston’s peppers as a commentary on vegetables.

Where Clarke imagines bleakness and despair, I can only see a fantastic and beautiful interplay of light and shadow – pure joy of seeing, in the same vein as Weston’s peppers, nudes and sand dunes, which are contemporaneous.

Both Clarke and Ian Jeffrey have a tendency to read more into some photographs than the photographer could have ever intended. That is one of the risks of writing about a visual medium.  Clarke may be at his worst in this regard as he devotes close to three pages to an image of a starving child being weighed in Mali, assigning virtually every detail in the  image with symbolism, from the face of the scale, to a lamp on the wall, to the angle of the child’s foot.

The problem of course is that, as any photographer can attest, the extraordinary difficulty of composing a shot, calculating the correct exposure (in this case a flash exposure in a poorly lit hut) and extracting the desired 1/60 of a second from any fluid, quickly changing activity is difficult enough. Photography is not painting and capturing the moment rarely lends itself to the kind of purposeful symbolism that photography critics are so fond of.

This particular image, like so many photographs, is powerful enough on its own terms, there is no need to  gild the lily.

But, if there are times when Clarke can be frustrating, he is always thoughtful and thought provoking. Do not get the impression that I did not enjoy Clarke’s book or that I would not recommend it. Just the opposite. It is an excellent book. I can be an argumentative cuss when it come to photographic criticism and one of the joys of Clarke’s The Photograph is that his thoughtful analysis provides so much to argue about.

Oxford History’s thought-provoking review of photography

The Photograph by Graham Clarke is the first of three planned books on photography in the Oxford History of Art series. The second is American Photography by Miles Orvell, which I’ll review at a later date. The third volume, Contemporary Photography, has yet to be published.

I was immediately disarmed when I started this book and read in the very first paragraph of the introduction Clarke’s candid acknowledgment of the inadequacy of a history of photography that is limited to 130 photographs in the entire book. In fact, what is also interesting is that while those 130 photographs include many classic images common to virtually any history, there are a number of selections that are a surprise.

Candidly, the book could do with a few more images. It seems as though the constraints of the overall series may have limited the selection a little too tightly. Some of the omissions are glaring. For example when Clarke devotes a chapter to “The Photograph Manipulated” he makes no mention of and uses no images from Jerry Uelsmann.

The Flatiron, 1903, by Alfred Stieglitz

Naomi Rosenbloom’s World History of Photography can be a gentle and relaxing stroll through the history of photography. But, Professor Clarke’s  interpretations occasionally made me want to scream, as when he discusses Alfred Stieglitz’s relationship with New York in his chapter on “The City in Photography.”

Clarke begins with an exploration of Stieglitz’s The Flatiron (1903), which he says, Stieglitz viewed as an image of the “new America in the making.” Clarke describes the image as “ethereal” and observes that Stieglitz “denudes the building of its solidity and function as an office. The realist context gives way to an imposed ideal frame of reference.”

A bit dense perhaps, but certainly accurate.

Then, Clarke turns to another image of the city taken some thirty-two years later: From the Shelton, Looking West. The image, Clarke says, is “sombre, still, bleak, and melancholy.

“Thus Stieglitz was effectively defeated by a city he sought to unify and idealize according to an underlying philosophy of meaning,” Clarke writes. “He rendered the social and human context neutral, and increasingly faced the material evidence of the city, not as symbolic image, but as raucous and callous reality of the kind we find in the paintings of the Ash-Can School, and in the naturalist writing of Stephen Crane and Theodore Dreiser.”

Not content to end there, Clarke concludes that this is “a made world always hovering on the edge of meaninglessness.”

From the Shelton, Looking West, circa 1935, by Alfred Stieglitz

This might be credible, if the image Clarke chose was remotely related to his conclusions. But, From the Shelton, Looking West is an absolutely beautiful image of sunlight playing against the sides of buildings. It may be “still” but it is most certainly not “bleak” or “melancholy.” (I apologize for the poor quality of the reproduction on this page, there were limited choices available on the internet, including some very savagely cropped versions that I refused to consider) Clearly, in the decades separating The Flatiron from From the Shelton, Stieglitz did more than probably anyone else to lead photography out of pictorialism  to the sharply focused, “straight” approach of photographers like Paul Strand, whom Stieglitz had championed.

The differences between the two images are evidence of how far photography advanced during those decades and how much Stieglitz’s own images reflected the revolution in seeing that he helped start. But there is nothing “raucous” or “callous” about the image and if it is not a symbolic image, I can’t imagine what is.

Stieglitz was never a chronicler of the human condition. Even The Steerage, which is about as close as he ever gets to social commentary, is as much about abstract shapes and interplay of light as it is about the passengers.

Clarke says of The Steerage, “there is no social or documentary concern. Stieglitz saw a picture of ‘shapes’, not of human figures, and concentrated on an abstract pattern which for him suggested the feeling he had about ‘life.’ The abject condition of the figures in steerage is completely ignored.”

Other authors might view Clarke’s assessment as a bit harsh. Ian Jeffrey, for example, sees the image as equally about composition and shapes and about the human condition. Jeffrey claims Stieglitz “warmed to the common people from whom he was cut off.”

The point really is this. Clarke’s strained attempt to inject social or personal commentary into From the Shelton seems to miss the point of the picture. It’s particularly perplexing because he certainly recognizes the purity of vision in The Steerage.  I see From the Shelton as a commentary about the city to the same degree that I see Weston’s peppers as a commentary on vegetables.

Where Clarke imagines bleakness and despair, I can only see a fantastic and beautiful interplay of light and shadow – pure joy of seeing, in the same vein as Weston’s peppers, nudes and sand dunes, which are contemporaneous.

Both Clarke and Ian Jeffrey have a tendency to read more into some photographs than the photographer could have ever intended. That is one of the risks of writing about a visual medium.  Clarke may be at his worst in this regard as he devotes close to three pages to an image of a starving child being weighed in Mali, assigning virtually every detail in the  image with symbolism, from the face of the scale, to a lamp on the wall, to the angle of the child’s foot.

The problem of course is that, as any photographer can attest, the extraordinary difficulty of composing a shot, calculating the correct exposure (in this case a flash exposure in a poorly lit hut) and extracting the desired 1/60 of a second from any fluid, quickly changing activity is difficult enough. Photography is not painting and capturing the moment rarely lends itself to the kind of purposeful symbolism that photography critics are so fond of.

This particular image, like so many photographs, is powerful enough on its own terms, there is no need to  gild the lily.

But, if there are times when Clarke can be frustrating, he is always thoughtful and thought provoking. Do not get the impression that I did not enjoy Clarke’s book or that I would not recommend it. Just the opposite. It is an excellent book. I can be an argumentative cuss when it come to photographic criticism and one of the joys of Clarke’s The Photograph is that his thoughtful analysis provides so much to argue about.

Share this: